Pacific Hurricane Season 2017

Battle to the Death – The Rare Fujiwhara Effect

Updated July 26, 2017 @ 6:40 pm EST

While the Atlantic continues to stay quiet for the month of July the Pacific is on fire with activity! Seven cyclones are enjoying their large party in this ocean basin and it is starting to become a little too crowded with all of this activity.

(Courtesy of Weather Underground)

The western Pacific just gave birth to its first Typhoon of the 2017 year. Typically three to four typhoons developed by mid-July in an average year (Dr. Phil Klotzbach; Colorado State University) making this a particularly quiet year.

Typhoon Noru finally reached typhoon status last week almost making it the latest typhoon to form on record in this basin. The record is still held by the 1998 season where the first typhoon of the year formed on August 3. Despite not breaking a record, Typhoon Noru still made headline news in the meteorological community and almost delivered a rare meteorological phenomenon: a Fujiwhara effect.

A Fujiwhara effect is the interaction between two separate cyclones that are close in distance to one another. When these two cyclones get too close they begin to orbit one another in a battle to the death. When a stronger/larger hurricane approaches a weaker one, the stronger storm usually absorbs the weaker/smaller storm. Yet, when both are roughly the same size, they act to influence the path of each other. One cyclone typically comes out the “winner” and suck the other hurricane into itself possibly making it larger or even stronger. This is a rare experience to witness in any ocean basin.

Noru, once reaching typhoon status off the southeast coast of Japan, immediately started to interact with another weaker tropical cyclone to the northeast: Tropical Cyclone Kulap.

(ECMWF (European) model forecast from July 23, 2017, of the potential Fujiwhara effect of tropical cyclones Noru and Kulap; Courtesy of The Weather Channel).

Noru being the stronger cyclone started to draw Tropical Cyclone Kulap closer to the point that each storm was revolving about a point between them, thus beginning the Fujiwhara effect.

(Courtesy of The Weather Channel)

While there was very little interaction between the two storms with regards to them orbiting one another, they briefly battled, with Typhoon Noru dominating. Typhoon Noru and Tropical Storm Kulap are continuing to interact with Kulap forecasted to dissipate soon as Noru feeds off some of the energy. The interaction between these two cyclones is not a true Fujiwara interaction however, since Typhoon Noru’s path won’t be affected by the other storm. If Kulap orbited around Noru it would have been considered a Fujiwhara effect. Instead, this was more of a slingshot effect. Noru instead is tossing Kulap around instead of them orbiting each other. Currently Kulap is down to a Tropical Depression with Noru still maintaining Typhoon status (equated to a Category 1 on the Saffir- Simpson Wind Scale).

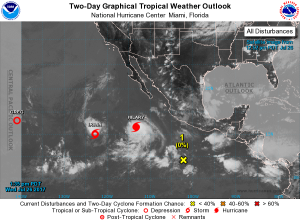

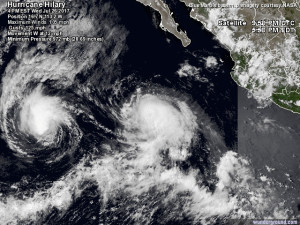

While this brief duel may be over in the western Pacific, another battle is about to take place on the opposite side in the east Pacific. Hurricane Hilary and Tropical Storm Irwin are about to have their own duel and possibly undergo a textbook case of the Fujiwhara Effect.

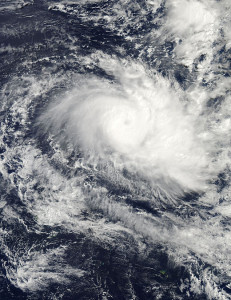

(Satellite Imagery Courtesy of NOAA)

These two cyclones are already so close to each and they are expected to move even closer in the following days. Hilary is the dominant hurricane in accordance with strength with a strong Category 2 status on the Saffir-Simpson Wind Scale. Irwin on the other hand is weaker, maintaining Tropical Storm strength. It is apparent that Hilary is much stronger and could win a duel based on this parameter. However, these hurricanes are close in size which is a large factor with the Fujiwhara effect. In the west Pacific, Typhoon Noru was much larger compared to tiny Kulap and therefore easily dominated the battlefield. Even though Trpical Storm Irwin is on the weaker side when it comes to intensity it still measures up in size to Hilary.

(European Model showing a possible interaction and Fujiwhara Effect taking place between Irwin and Hilary in the coming days; Courtesy of Weatherbell Analytics)

Computer model projections, like the one above, show these two storms nearing each other and possibly interacting beginning Wednesday July 27, 2017. The storms will begin to orbit one another with Hilary rotating counter-clockwise around Hurricane Irwin, the start of the duel. One will likely cannibalize off of the other.

Luckily these two systems are far away from land and pose no threat. However, western Mexico and southern California can expect to see some high surf for the next few days as these two storms battle to the death.

The Pacific is clearly coming alive and showing some rare features this year, and it has only just started. Place your bets on the battle between Hilary and Irwin. Who do you think will win?

What is up with the Hurricane Drought in the Southern Hemisphere?

Updated February 4, 2017 @ 7:21 pm EST

You may have scrolled through your news feed and ran across a few articles stating a “record-smashing hurricane drought”. Indeed, the southern hemisphere is experiencing a case of “missing cyclones”. For over 280 days the Indian Ocean and the southern hemisphere of the Pacific Basin have not seen a cyclone develop with winds exceeding 74 mph (equated to about a Cat. 1 system on the Saffir-Simpson Scale for the Atlantic).

The southern hemisphere typically sees cyclones form between November and April each year. April of 2016 (the end of the previous cyclone season) was the last active month for cyclone development in these ocean basins where we saw Cyclone Fantala (Indian Ocean) and Cyclone Amos (Pacific Ocean).

Courtesy National Hurricane Center and WeatherUnderground

First Image Cyclone Amos – April 22, 2016 (Cat. 3 on the Australian Cyclone Scale; Cat. 2 on the Saffir- Simpson Scale).

Second Image Cyclone Fatala – North of Madagascar April 18, 2016 (Very Intense Tropical Cyclone on the South-West Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclone Scale; Cat. 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale).

Cyclone Amos and Cyclone Fatala were the last two of the “2016 southern hemisphere hurricane season”, however when November 2016 came along, the opening of the 2016-2017 cyclone season, everything was quiet. A few disturbances were noted around Australia and the Indian Ocean but none of these systems ever strengthened to hurricane status. Going through the Hurricane Archives in WeatherUnderground and UNISYS, the south-west Indian Ocean has so far seen 3 depressions (lows) and 1 tropical storm strength system (Cyclone Abela); the Southern Pacific Basin has seen 8 tropical depressions; and the Australian cyclone region has seen 15 depressions (lows) and 1 tropical storm strength system (Tropical Cyclone Yvette).

Since the start of this current southern cyclone season (2016-2017) no hurricane strength systems have formed in any of the active southern hemisphere regions. So what is going on?

(November and December 2016 Average Sea Surface Temperatures (SSTs)- Courtesy of NOAA National Centers for Environmental Informations Data Base)

Let’s take a look at November and December of 2016. The SSTs in the Indian Ocean were already below average for this time of the year, a bad sign for tropical cyclone development. This cool area spread from Madagascar over to the west and south of Australia, areas which are known for cyclone development. Although SSTs for the full month of January 2017 is not yet available we can look at the most recent SST anomalies from Weather Underground:

Global SST Anomaly Generated January 25, 2017

The pattern remains the same as November and January. The Indian Ocean remains cooler than normal and now we can see that the east side of Australia (surrounding New Zealand in particular), which is following the same pattern at the Indian Ocean.

Immediately this is one of the reasons cyclones are not forming/strengthening in the active cyclone areas of the southern hemisphere. No matter what ocean basin, a hurricane needs water temperatures to be around 26.5 degrees Celsius in order to form and strengthen. At the moment, we are not seeing these temperature values in these active areas.

In addition, meteorologist Michael Lowry commented that the Indian Ocean in particular has been seeing intense upper level wind shear values which are hindering cyclone development in this particular area:

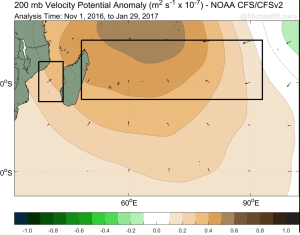

200 mb wind shear levels. Darker browns indicate high levels of upper level wind shear (courtesy of Michael Lowry – Twitter).

High levels of wind shear have dominated the upper layers of the atmosphere off the northeast coast of Madagascar from November, 2016 thru January, 2017 contributing to the lack of cyclone development.

In addition there are two more culprits to blame for the quiet southern hemisphere: the weakening of the Pacific el Niño and the general geography of the southern hemisphere.

It comes as no surprise that the el Niño (which peaked in 2015) is coming to an end. In fact the Pacific is now leaning more towards a la Niña phase (though very weak).

In September of 2015 el Niño was around its peak intensity, with high SSTs hugging the west coasts of North and South America. The cooler waters retreated westwards towards Australia due to this climatic event. This el Niño fueled cyclones in the Pacific and we saw the very active 2015 Pacific Hurricane Season because of this warm ocean water (everyone remember Hurricane Patricia?)

The el Nino event showing high SSTs in the eastern Pacific during September 10, 2015 (Courtesy NOAA).

However, the 2015-2016 el Niño began to fizzle along with the very warm waters. In it’s place a weak la Niña event formed starting around the summer of 2016 and began to cool the waters off western South America. It is not a drastic cooling, and thus we label this as a “weak” la Niña event. Nevertheless, it is a sign that hurricane activity would not be as active in the Pacific Basin and this is why the 2016 Pacific Hurricane Season was considerably less active compared to the 2015 season. The la Niña is still continuing and is cooling the eastern Pacific. Ideally warmer waters should start to drift westward during this cool phase, but because of how weak the la Niña event is, there is no real change taking place. We could see warm waters start to move westward in the coming months in preparation for the 2017-2018 Southern Hemisphere Cyclone Season but we will not know until summer time (in the northern hemisphere) if this will occur. Additionally, it is possible that the la Niña event will strengthen a bit more, pushing the warmer waters westward and being replaced by cooler waters in the eastern Pacific.

One final note that many tend to overlook: the geography of the Southern Hemisphere. Immediately, we know that the biggest difference between the two hemispheres is the distribution of land and sea. The northern hemisphere has more land mass while the southern hemisphere has more ocean. Land masses absorb more heat compared to the oceans which are generally cooler than land. Therefore, because there is less land in the southern hemisphere it is generally cooler on average compared to the northern hemisphere.

In addition, land plays a large role in wind speeds. Mountains help to break apart winds and even lessen wind shear. In one way the mountains help block “harmful” winds that could break apart a developing hurricane. The main benefit with more land though would be higher temperatures, perfect for hurricane formation and growth. The southern hemisphere lacks land mass and therefore mountains. The southern hemisphere is thus cooler and contains more wind shear, two ingredients that don’t make a “happy hurricane”.

The cyclone season for the southern hemisphere is still ongoing for another 3 months, but so far it is dead quiet with no areas under investigation (as of Feb. 4, 2017). January and February tend to be the active months (max. summer time in the southern hemisphere), so if a hurricane were to form, this is the ideal time.

February is the time when major cyclones begin to form and at the end of the previous Southern Cyclone Season we saw a rare occurrence that took place in South Pacific Ocean: Tropical Cyclone Winston. First, it is not uncommon to have a cyclone/hurricane develop outside of the November – April time frame, especially in the Pacific. The West Pacific Typhoon Season is usually active all year, but this is mostly for the northern hemisphere. In February 2016, Tropical Cyclone Winston formed in the Southern Hemisphere and grew to be a Cat. 5 Severe Tropical Cyclone on the Australian Scale and a Cat. 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale. Winston became the strongest tropical cyclone to make landfall in Fiji and the strongest cyclone to form in the Southern Pacific Basin.

Severe Tropical Cyclone Winston – Cat. 5 nearing Fiji on February 20, 2016

Winston was the last major cyclone the southern hemisphere saw during the 2015-2016 southern cyclone season.

Winston is a reminder that severe cyclones can form, especially during the month we are currently in (February). Just because it is so far a quiet cyclone season, does not mean the rest of it will be. Regardless of if a hurricane forms tonight (highly doubtful) the 2016-2017 Southern Hemisphere Cyclone Season has smashed all records for being the quietest year. The previous record for the longest streak without a hurricane was in 1988.